In August 2002, the Abaco Barbs were designated a new strain of the critically endangered Spanish Barb breed by the Horse of the America’s Registry. The 8 remaining Abaco Barbs, on the island of Abaco in the Bahamas, are fighting for their lives as human intervention and a drastic change in habitat have taken a severe toll.

The struggling remnants of a once mighty herd of 200 are facing extinction for the second time in their recently turbulent history. The Government of the Bahamas designated a preserve area for the horses and the four remaining mares and one stallion are now back in their normal habitat. The other three stallions are waiting for the next expansion of protected area.

The History of the Beautiful Abaco Barb

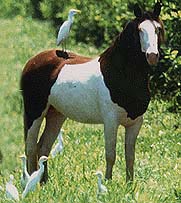

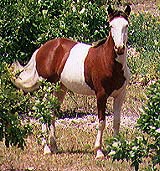

Once, they were a mighty herd, perhaps 200 strong: pinto, bay and roan horses rippling through thousands of acres of pine forest. They were as free as the sea winds that blew across the island they had conquered.

Their origins remained unclear until 1998, when it was recognized, by a few individuals, that the horses probably were Spanish Barbs. In August of 2002, based on three separate DNA analyses and photo and video records, the horses were accepted by the Horse of The Americas Registry as the Abaco Barbs, descendents of horses brought over at the time of Columbus's explorations.

Throughout the world Barbs are recognized as critically endangered. The Abaco Barbs nearly went extinct in the early 1970's. Today they are once again fighting for survival. The horses have been returned to a preseve in their ancestral forest home. Their history, as we know it today, follows.

Few horse wise people would have expected those domesticated horses to survive in this place. Whether you come by air or by sea, this does not look like horse country. After years of being fed, groomed and cared for, suddenly the gates were open. The halters were gone. The mangers were empty. After a sea voyage that could have lasted six weeks or more, with little food or water to reduce manure they either were wrecked or abandoned on this island.

The horses stood for a while, blinking in the sun. It grew hotter and hotter as the sun rose. Slowly, they moved off seeking shelter, food, and in the manner of horses, companionship. And survive the horses did, as they had been bred to do under appalling conditions. In fact, they flourished. They came from sturdy stock, with compact bodies and strong legs. Long tails and flowing manes and gleaming coats made them beautiful.

Abandoned on a sun-drenched and salt-seared island, they found shelter in pine forests

The pine forests of Abaco are something few visitors know exist. In the Bahamas, the Caribbean pines (Pinus caribaea), exist only on Grand Bahama, Andros, Abaco and New Providence Islands. On Abaco, the forests provided a home for the tough, romantic and equally rare wild Spanish Barb horses.

In the dappled shade of the pines the horses escaped the burning sun. They tramped out a network of pathways among the grazing places and the sloughs and springs where they watered. The pine forests had for millennia sheltered flocks of wild parrots and migrating birds. Scores of species of orchids, other plants and thousands of insects lived in the forest. The forests sheltered the wild hogs, also abandoned by the early settlers, and they sheltered the horses.

In addition to shelter, the forests provided food. After fires set by lightning bolts swept away the underbrush, fresh grasses sprang up and provided a change of diet from the grasses that grew in open areas.The nourishing grasses probably had arrived as seeds in the crops of migrating birds Even in the worst droughts the horses had water. They had enough room to roam and graze, and they grew sleek. Only an occasional horse was lost to people from the outer islands who captured a few for work at sugar cane mills.

Then, in the 1960's, disaster struck. Neither a hurricane, nor a catastrophic drought nor a tidal wave. No impossible fire, flood or disease. A road. A simple road was carved out of the chalky limestone surface of Great Abaco. A road running from one end of the island to the other so that Owens-Illinois could harvest the remaining forests for pulpwood. The shelter of the pines was shattered.

Suddenly humans had access to miles and miles of long-abandoned but still passable logging roads from earlier operations. Sometimes people ran the horses down these narrow roads until they were close enough to be roped out of the windows or until they dropped from exhaustion. Many of these animals became legends, for their anecdotal lives, the vicious cruelty visited on them, and their tragic ends.

A tragedy involving the death of a young child who tried to ride a tame wildhorse while unattended resulted in a wholesale slaughter. Former Senator Edison Key said in an interview, "When we were clearing the land for the farm in the early 70's, we found carcasses and bones everywhere. I started thinking. It just wasn't right."

At that time two wild mares were still alive at the farm, Liz and Jingo. A pinto stallion named Castle was brought up from Marsh Harbour. Those three horses were lucky. They were able to share buidlings, shelter, feed, grass and grain with the cattle on the farm. When a vet came to check the cattle, he checked the horses.

One farm hand was assigned to the horses full time until they became acclimated and were released. Today's horses, descended from the last stallion of the original wild herd, returned to the pine forests. The herd is growing slowly in spite of wild dog attacks which kill several foals a year. The farm now covers 3000 acres and the grasses imported for the cattle have spread. In the savannah-like areas of the farm -- planted in limes, grapefruits and oranges -- are acres and acres of forage the horses relish.

In 1992, the future seemed bright. However, by 1997 the herd had dropped from over 30 to 16. Individuals horses previously identified, and known by sight had vanished. Corpses and skeletons were turning up in alarming numbers. As usual, it is human pressure that causes concern and it is the goal of the Abaco Wild Horse Fund to try to remove that pressure. By 1998 with the survival of four fillies, the herd was up to 21. It is hoped that this is a trend, and not a glitch .

And the horses, to be truly wild, need the forest. They survived before without the farm. The forest shelters the horses from the sun. The limey outcroppings keep their hooves pared down and naturally trimmed. After a burn, the forest floor is covered with succulent new grasses for forage. If the horses are to remain wild, some of the forest must remain wild too.

The AWHF, working in conjunction with the Boy and Girl Scouts of Abaco, hopes to have the forest surrounding the farm declared a preserve. Wildfire is a critical part of the wild forest cycle.

But too many of these fires are started by man to clear land for cultivation and to drive hogs from the dense brush. Although often severely charred, adult pines are seldom killed by flames. The younger pines are less fortunate, though reseeding takes place quickly aorund the bottoms of the adult trees whose pine cones are burst open by the heat, thus releasing the seeds. But constant, deliberate burning will upset the forest cycle. New pine growth will burn with the brush and the juveniles will never get a chance to mature. Orchids and wildflowers die out.

The saga of the wild horses and their home in the pines teaches several important lessons. Left to their own devices, things tend to seek a natural balance. Over-hunting, over-cutting, over-burning all upset this natural order and the inevitable result is too much dying. The inevitable result of too much dying is extinction. Many people feel that the horses' survival may point the way to a better future in Abaco.

The Abaco Wild Horse Fund, Inc., established to help support the wild horse herd, gains support for its Projects by offering Gift Sales, and a How to Help section. In addition, a portion of the profits generated by sale of items through ARKWILD is donated to the fund. Questions and comments welcome, Send E Mail.

|

|